No more ACT or SAT writing? Most colleges and universities are cutting it out. Good news? Maybe, maybe not. College admissions essays are becoming more important not only for them to know you, but as to how they judge your ability to write.

For a growing number of schools, they’re not just a profile of who you are as a person. They’re also being used to see if you can write and redraft at a college level, effectively replacing the standardized tests’ essays.

Computers have been a quiet part of the admissions process for a couple of decades, but now they’re part of the race to stay in the good graces of the bottom-line rankings of U.S. News & World Report.

With the exception of Hampshire College, which dropped out of the ranking rat-race, the name of the game for the other 99.95% of schools is upping their all-important number in the pecking order of the U.S. News & World Report’s College Rankings.

Colleges want better prospects who have a higher likelihood of attending, and a means to pay the ever-escalating costs of tuition. They also need to achieve the diversity of interests, of specializations in the academic community, and fill out their needs for athletes, artists, musicians, etc.

Increasingly higher ed is being forced to turn to computers to crunch the overwhelming number of applications annually.

APPLICATION AVALANCHES

Schools receive a ton of applications, thanks to the Common App, Coalition App, and the Universal App. Computerization has turned applicant puddles into raging rivers and future freshmen reservoirs that could overwhelm the Hoover Dam.

Many of the highly selective, smaller schools will tell you that they read every application “holistically,” that they look at everything about you, including your essays, without any pre-screening.

Every app.

The process traditionally has looked like this sneak-peak into the process at Amherst College.

That system was easy in the days of paper applications, because the physical process and expense of mailings kept the applicant pools for schools at manageable levels.

Today, though, both the top highly selective colleges and super-sized state universities will annually receive between 20,000 and 40,000+ applications each.

At $85 a student, an ivy league school that receives 32,000 applications generates roughly $2.6M dollars in revenue, just for the privilege of applying to their school!

Getting students to apply in large numbers is good business. Aside from the big payday, it means that they get a much broader and diverse pool of great students from which they can choose.

Holistic reading, reading of the whole file is a Cadillac feature of the process at the selective schools. The idea that every inch of every file will be considered is a big draw to attract top students, especially at the top of the pile, the “highly selective” schools.

TRADITIONAL ALGORITHM WEEDING

Most schools do not claim to review all files holistically. Instead, they use algorithms that filter out students with low SAT scores, or GPAs that don’t meet standard for the “NO” pile. The algorithms suggest the best of the best for automatic admission, the “YES” pile. They then score the students in the “MAYBE” pile based on comparatives of high school students to past students at their schools over time in terms of academic rigor, extra-curriculars, etc. The ones within the range of applications that these schools are geared to read, in a range of an estimated 6,000 to 10,000, are then sent for manual read.

Colleges are adopting algorithms not only to process applications, but to evaluate courses, student performance, and improve outcomes. Services like eLumin are able to target data for academia that benefit everyone in the educational process.

THE COLUMBIA CONUNDRUM

To illustrate the challenges schools face in dealing with a daunting number of prospects, not pick on Columbia University per se, let’s use one of the nation’s best, and most highly selective schools’ admissions program because they DO make a claim, at their campus info sessions in 2017, at least, that they holistically read every file.

Every last one.

Is that even possible?

Let’s take a look how that process might work to illustrate how technology could find its way into the most in-depth end of the admissions process, where efficient essay examinations have been the final frontier of the process in an era of volume applications.

According to Ivy Coach, Columbia University received nearly 32,000 applications in 2016.

According to Ivy Coach, Columbia University received nearly 32,000 applications in 2016.

So how do they read that many, end-to-end?

While we’ll never get Columbia to describe its closed-door process, we can do a little back-of-the-napkin figuring to see if “holistic” and “human” match up. Bear with the math here, for a moment, because it is interesting to not just take claims at face value, but to consider what it takes to get the result of a quality “holistic” read of your college application.

Completely manually, it takes roughly 10 minutes for an admissions officer to “do” a file. Figure a read of the digested material by the algorithms doing number crunching makes it a bit faster, but in that 10 minutes, assume that 2-4 minutes will be used to read the essay, and another minute or two for the supplementals.

Last, the reader will score the file and write any notes about the applicant should the student remain in consideration in the MAYBE pile.

Without breaks, phone calls, etc, at 10 minutes per, that’s roughly 5,300 man-hours for one person to read all 32,000 applications! If they worked a forty hour week, and never left their desk, it would take 133 weeks for one person to read all of the files once in a pool that large!

So, there has to be a way to break that down more, right?

Right, well, sort of.

Essays are personal. To make them a meaningful part of the admissions process for a college of Columbia’s high standards, the human factor of reading, and discussion by those readers, really has to come into play.

Decisions are personal. Humans very much are the trigger-pullers of the overwhelming majority of college admittances.

The university doesn’t advertise the number of admissions staff and readers which it employs. A large office that reads holistically might have 15 admissions reps, though, and possibly another 10-15 readers, students whose work-study is to digest and comment on files to aid the process.

They generally don’t hire too many readers, because, after a while, the size of the teams becomes so unwieldy that there are too few people at a meeting where final decisions are being made that have actually had their eyes on a student’s file.

If Columbia does a ‘tiered’ read, which is possible, then add even more man-hours to the process as the admissions officers would probably have to re-read the files that they didn’t pre-screen.

Divide the labor by 15 admissions officers, on a single-pass, holistic read of the files, and it takes about 353 man-hours, or 9 weeks for all of their staff to have ONE person read the files. That’s enough to get the job done in the time that they have.

Wait a minute, though.

One person doesn’t read your file. There are usually three to five people who read an application, to provide different perspectives on the applicants, prevent bias, and discuss the MAYBE pile in an informed way.

Hypothetically, three teams of five admissions officers would have about 1765 man-hours, per team, per person to do a human, holistic read of all of the files.

It would still take each of those admissions teams, reading at full tilt, no breaks, 44 weeks to have multiple readers go through so many files completely manually,”holistically.” Even amping up the staff to 30 people would cut it to 22 weeks, not the typical 10-14 week cycle most schools use.

Plus, admissions officers are often out speaking to schools, running info sessions, and, at some point, they need to actually sit down, meet, discuss, and whittle down the final candidates and, oh, admit people.

So, if Columbia is being, as we assume, 100% honest about that holistic read, then the process likely has an assist or two going for it.

“Holistic,” then, doesn’t necessarily mean “human,” if a school can use a computer algorithm to aid in holistic reviews all of the applications in a massive applicant pool.

THE DAWN OF THE ESSAY ALGORITHM

We’re seeing the shadows of essay-reading algorithms entering admissions not just at the holistic-read schools, but at the larger universities as well.

At some super-sized state schools, including University of Central Florida, that have 36,000 applications for about 6,500 undergrad admits, applicants for 2017 were being admitted three days after their “early” Florida resident applications deadline closed.

That could be early reads of the first apps coming in by humans, but a few things suggest otherwise:

- UCF has had its Florida student early admit deadline for years and has always waited until the first week in December to notify everyone;

- There are a TON of fall college fairs and admissions reps are busy in recruiting mode. They would have to read in their evening or off hours while traveling, which could be done via a computer network, but is both not secure and a lot of extra work for admissions officers meeting for hours a day with students, guidance counselors and going to college fairs;

- They get a lot of applications in that first wave, and early admit based on timestamp without something that helps shape the admissions process would be haphazard and not produce good outcomes. What if the person from week 3 of early season is far better than the person from week one’s pile, yet you admitted on time stamp. That makes no sense;

- Quick algorithm reviews allow the easy “yes” pile to clear ASAP and gives students the knowledge that they have a school just days after the close of the first deadline, which is great “curb appeal” for a large school, and allows faculty in sports and the arts to snag great students because they are already pre-qualified to get into the front door of the University.

This new move to early admit, rather than just a change of policy, would hint that algorithms are being used to do basic reads and scoring of essays that lighten the load on admissions officers.

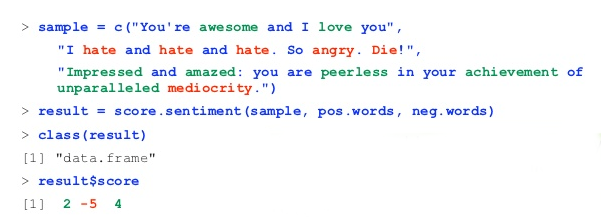

BRAVE NEW WORLD OF COMPUTER READERS

Computers at many of the universities to which you will increasingly be applying algorithms, sophisticated programs, to your essays that operate much as they do at those free websites which allow you to check the quality of your essays and papers before you submit them in high school.

These programs can search not just for keywords, but for form, content, style, cogency, and even your contextual word and sentence choices.

Many of those “free” sites that you use to evaluate your essays have been quietly teaching computer algorithms. Companies like Pearson gather essay data to teach the programs the nuances of the English language.

THE DARK ARTS OF ADMISSIONS?

Schools sell personal attention in their pitches to prospects. They have to make you believe that you are going to be a unique individual, not just a cog in the wheel.

Schools sell personal attention in their pitches to prospects. They have to make you believe that you are going to be a unique individual, not just a cog in the wheel.

So discussing back-office systems like admissions algorithms is anathema a part of the Dark Arts of admissions that colleges don’t generally like talk about, much like people in Fight Club don’t talk about Fight Club.

Yet, the math and the calendar both tell us that algorithms are helping, if not acting as the primary gatekeeper to the process of actually reading college applications’ essays and supplementals.

The Upside of Algorithms

It should be pointed out that use of algorithms by college admissions offices isn’t a bad thing. The goals of using technology to aid the process are not evil nor are they dehumanizing.

The process is geared to find the better 30-40% of the pool, and concentrate the humans’ time and attention on more likely candidates where they can digest, discern, and debate their merits, rather than cramming thousands of applications, should be welcomed by those who, one way or another, would have a fighting chance to gain admission.

To the plus side, if an algorithm pre-screens files, that will allow a few people, who might have been weeded out by simple academic number-crunching filtering, to stay in the applicant pool.

This is why, though, your essay becomes even more important, because computers use a lot of yardsticks to evaluate you not only in terms of keywords that the admissions officers might like, but also to score the strength of your written expression.

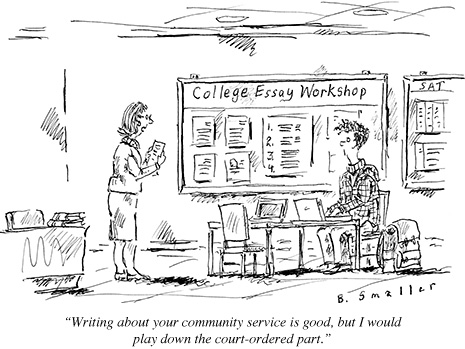

YOUR Essay IS THE CRITICAL Sample OF YOUR ABILITY TO WRITE

No matter how they score your essay, human or computer, essays are taking on a much more important part of your path to colleges.

No matter how they score your essay, human or computer, essays are taking on a much more important part of your path to colleges.

You may have heard that many colleges are dumping the supplemental SAT/ACT writing sections?

Yea!! Well.. maybe.

We’ve been able to get a few colleges’ undergraduate admissions offices to confirm that they see your college essay as a representative writing sample of you, the applicant.

Their thinking: You have months to complete your essay, and you should have gone through multiple passes to draft and redraft it.

Redrafted essays are more representative of how most college essays are written, rather than the SAT/ACT timed model.

How far you get in the admissions process, to get seen by human eyes, and have your words experienced as part of your total “package” depends in a growing part on how well you write.

How the Essay Can Improve Your Chances at Admissions

Start in Junior Year

You should not wait until the last few weeks to work on your essays. We’ve read hundreds, and the best, with the best clearance rates of their college choices, tend to be started during the JUNIOR year, usually towards the spring of that year, after APs are over. Colleges in their admissions information sessions are repeatedly advising juniors to start earlier. It’s not a suggestion. It’s a warning. Take it seriously.

EVERY WORD COUNTS. EVERY IDEA. EVERY PARAGRAPH.

Spelling, proper punctuation, word choices and the cohesion of your ideas into paragraphs, paragraphs into the totality of the essay all can be scored to show how competently you write.

Spelling, proper punctuation, word choices and the cohesion of your ideas into paragraphs, paragraphs into the totality of the essay all can be scored to show how competently you write.

The comma is your friend. It tells us to take a breath, or groups a sub-thought, like this one, so it is easier and faster to read. Beware of the use elipses “…” and parentheticals “().”

Wrong: “I knew that George thought (As he always did.) that I wasn’t serious about getting in that airplane with a parachute on my back.”

Right:“I knew that George thought, as he always did, that I wasn’t serious about getting in that airplane with a parachute on my back.”

Both are technically correct grammatically, but anything that can interrupt flow (As parentheticals like this can) might cause your tired college essay reader on their 30th of the day, whizzing through your essay, to lose track, stop, and re-read. Then you lose them.

Word Choice

A thesaurus isn’t a vocabulary dinosaur. It’s a vital tool. We may need to repeat a word or idea several times in a paragraph. The problem with using the same word over and over is it can cause “skipping” for a tired reader, that loses their place. It also can score you down in computer evaluation. Use a thesaurus to see if you can find a way of not repeating yourself over and over in a paragraph:

First Choice: “I’m excited about meeting my dorm roommate. The dorm experience is where I will find the other part of my school experience, and roommates are important to your college experience.”

Thesaurus-infused: “I am excited about meeting my first roommate. The dorm is a huge part of a college experience, and the person with whom you live every day is going to be a huge influence on day-to-day life in school.

Remember, though, not to toss in words that you have no idea how to use, or use in context. Computers can pick off pseudo-pretension, as will human readers:

Wrong: “It elated my discernment of wondrous math.”

Right: “I was elated because I understood, for the first time, the wonder of being able really grasp the language of math.”

Hook, Support, Close

What grabs the attention of the reader? An ENTERTAINING, clear, concise idea of what you’re going to be talking about, and uses descriptive, even sensory word choices, time and place well. Dull essays score down, and read poorly.

Wrong: “I have always been an avid fisherman, but I almost died one day because I forgot to put fuel in the boat when I set off early one morning.”

Right: “Bait? Check. Gear. Check,” I thought to myself as my hand slipped on the wet deck, pushing off from the dock in the dark of early morning. The boat growled quietly as I navigated the glass-calm waters of the Intercoastal for a day of fishing off the coast of West Palm. The multimillion dollar mansions on the beach were tiny dots on the bobbing horizon when I saw it, and froze: The fuel gauge was near empty. In my mind’s eye, I could see the spare gas can sitting in the boat dock locker, right next to the broken emergency radio I was meaning to replace. Oh, this was not good.”

The Written versus Spoken Word

In his book “Doing Our Own Thing: The Degradation of Language and Music and Why We Should, Like, Care” linguist John McWhorter shows us how Americans were once educated in the understanding of the written versus the spoken word. He shows us a letter written by a steelworker on the Brooklyn Bridge from circa 1870 to his girlfriend. The language was precise and proper, and would be nothing like the way that he spoke as a blue-collar steel guy from Brooklyn.

We are not generally taught to separate our written and spoken thoughts as much anymore. As a result, most students writing college essays tend to use a LOT of conversational conjunctions in long run-on sentences: “and” “and” “and”

The paragraph connects ideas together, sentence by sentence. Paragraphs placed in the right order create the next level of flow. The hook, supporting paragraphs, and close make up a simple essay.

Wrong: “I believe that eating meat is why there is so much obesity in America today and environmental problems from raising a lot of cattle and chickens all over the world. I would like to become a dietician or maybe a nutritionist who works with obese children because obesity in children is out of control. But I think that I can do something, if I go to your university, to help stop that.”

Right: “Americans’ huge appetite for meat for meat has created an obesity epidemic, and an environmental catastrophe. I would like to investigate ways to change world diets. A reduction in the consumption of meat will help millions of children lower their intake of harmful fats, and too much protein. In turn, reducing animal consumption lowers production, and curbs greenhouse gas emissions.

Redraft Essays Multiple Times.

We tend to write in a stream of consciousness, getting ideas out of our brains as they come. The writing becomes more relevant as we write further, and sometimes, what is really the “lead” idea comes out after four, five or six paragraphs of thinking!

It is rare, even amongst the best adults who are professional writers for decades, that people can single-draft an entire essay perfectly.

It’s even harder when you’re trying to talk about yourself, and your life, something which most of us are both unaccustomed to doing and a bit uncomfortable with.

Redrafting is an essential process of writing a college level paper. Your essay should be able to reflect that you can do that competently. It gives you the ability to keep writing and refining until you discover the things about your story that are really important, and then organize them into something concise and tight that will allow the college to understand you in the 2-3 minutes that they have to absorb your life.

Essays should be highly personal.

The better essays talk about fairly private things, personal challenges, family issues, health issues, struggles with one’s identity, that “epiphany” moment when you realize what you want to do with your life, or you don’t, or you discover something about yourself that changes the way that you see the future.

You may start by telling a very external story, and think that’s good enough. The question is, how many other people are telling their story that generically? Does that separate you from others, or make you blend in?

In high school, blending in may be good. In college essays, not so. Your essay must be about you, uniquely.

Your essay must be about you, uniquely.

Schools get hundreds of “How my Bar Mitzvah made me a man,” or “How I overcame injury as a dancer/athlete and learned from it.”

We tend to hide ourselves in bigger tales of yardsticks in the activities of our lives that shape us, but do not define us. This is also why drafting is so important.

The new computer screening systems will continue to get better at scoring essays for interest levels and uniqueness. It’s also better for the human readers, who make the final decisions, to make you a player in their diversity search.

So tell your story honestly. Are you a notable nerd D&D gamer? The shy quiet kid who has a musical going on in your head all day that you would write if you had the time? An ice skater who has always dreamed of being Minnie Mouse in a Disney on Ice show? Establishing your identity in some new way? That IS you. Don’t hide it. Talk it up. You want to show the colleges and their computers thumbprint, not generic barcode.

A PERSONAL JOURNEY

Essays for college are best not written in school and/or peer reviewed. College essay practice is great in school, to learn the process, but you should work on your college essays ALONE, in your own way and time.Everyone discovers more about themselves in high school intellectually and socially. Some of that may include very personal things that you do not want to share with teachers, or especially in peer review.

Essays for college are best not written in school and/or peer reviewed. College essay practice is great in school, to learn the process, but you should work on your college essays ALONE, in your own way and time.Everyone discovers more about themselves in high school intellectually and socially. Some of that may include very personal things that you do not want to share with teachers, or especially in peer review.

Having friends help you with your essays isn’t always good either.

If you share common essay ideas with friends, or someone peer reviewing likes a passage that you wrote and plagiarizes it, and you all apply to the same schools, the human readers might miss it, but the new computer algorithms searching for cheating and plagiarism have a good likelihood of picking it off and disqualifying you all.

Neither a Borrower nor a Plagiarist Be

There are students who think that they can game this process by using the work of others. Essays of older siblings, friends who graduated a year or two earlier, who didn’t apply to the same schools as you are applying, or essays found in the ‘dark alleys’ of the Internet all get re-written a bit, or not at all, and submitted.

With thousands of essays and human readers, you might get lucky, but with computers evaluating your work, databases of these things build up.

At this time schools don’t share access to each others’ essays. If, however, several of them contract with a plagiarism detection service, and that service confidentially cross-references samples, if you “borrow,” from a past essay in part or in whole, not only that college is apt to drop you, but any other college notified of it. There are no easy shortcuts to writing a great essay.

THE SCHOOL FORMULA ESSAY

There are English/language teachers who have had students with a bit of success with a particular essay format, so they teach that “winning” essay that’s almost plug-and-play.

There are English/language teachers who have had students with a bit of success with a particular essay format, so they teach that “winning” essay that’s almost plug-and-play.

Those were reasonably effective in the days before computers, unless one reader got two or more of them in the same batch, or they showed up in the final rounds of consideration and the tactic is discovered.

“Canned” essays either for format or language style, can easily be detected both by computers and human admissions staff. Don’t use them, or any fraction of someone else’s “system” beyond the basics of opening hook in the introductory paragraph, development of ideas, and your close.

Your essay can be scored for originality and uniqueness by a computer system. Don’t assume you can end-run that game.

HELICOPTER ESSAYS

Readers and computer algorithms are good at picking off “helicopter” parents’ hands in essays like a surface-to-air missile.

Essays that are overly focused on major choices, especially in engineering, medicine, law, or business, just reek of parents’ peddling of professional preferences.

These essays become so external to the student that they fail the task of getting one or more of the readers to want to admit a student. There are a lot of helicopter parents, so helicopter essays are a dime a dozen.

Parents’ helpful suggestions about talking up the school, an alumni affiliation, or a legacy usually backfire as well, as there are places for students to put that into the app outside of the essays.

There are places where one can indicate their major preference. The essay is not a defense or explanation of your major choice directly. If you are interested in marine biology, you can talk up your summer counting fish off the keys for your dad’s friend who works for Fish & Game, but don’t then try and link it back to your marine biology major. Assume the admissions readers are smart enough to connect the dots.

If you are worried about the suitability of an essay, ask the guidance counselor, or a college counselor or consultant, to give it a read and then give you their take on it.

THE [YOUR NAME HERE] MANIFESTO

Great college essays are a personal manifesto of purpose, or inspiration, or aspiration of your separating young adult.

Great college essays are a personal manifesto of purpose, or inspiration, or aspiration of your separating young adult.

Students may, or may not, wish to share essays with their parents.

Parents: Do not take this as a personal sleight. Your student is often trying to work this essay out in their own minds, on their own terms. They have to factor what their experience over the last four to eight years means, and how it can attract the colleges’ attention.

A story about a life experience that may not be suitable to their current living situation, but is part of where they see themselves heading, may indeed be the factor that helps them gain the college readers’ attention. Stories about family sometimes are great for a reader to get to understand where a student is coming from, but their observations of family life may not always be appreciated.

PARENTS CAN BE HELPFUL

Students need to be aware of where parents can be genuinely helpful. Sometimes an essay revolving around a family story gets a big boost when students realize that mom, dad, and siblings all had different, sometimes even very warm and funny takes of the same event. Anything that humanizes you will score well with the algorithms and the human readers alike.

GET EXPERIENCED EYES

Guidance Counselors/College Counselors or College Advisors are all great resources for shaping general ideas and avoiding pitfalls – Extremely connected to the process, and, like your doctor, independent of your peers and your parents, great guidance and college counselors can provide you a lot of ideas about how to find a topic for your essay, or how it’s shaping up. They can be good sounding boards because they understand the confidentiality of the process, and their only goal is to help you get into a college or university. The best ones will help you to tailor your essays so they shine best in one system or the other. Still, they’re only human too, and their advice may not fit your vision of how to do this right.

Tailoring your Tales TO MAN & MACHINE

There are many schools on the Common/Coalition/Universal App systems. So your primary essay needs to fit all schools on those systems. The supplemental essays unique to the schools are where you need to talk about yourself. Keep in mind:

- The kind of school(s) to which you are applying. What the “vibe” is of their campus, their programs, etc.?Hampshire might appreciate your brutal honesty about discovering your calling as an eco-warrior, but Oral Roberts may not feel as warm and fuzzy about the topic.

- Be clearer for the algorithm. Many times we use a lot of personal pronouns because we know what we’re talking about. Humans can usually also fill in the blanks. Algorithms, in this regard, are kind of stupid. So, make sure that, whatever is attached to a personal pronoun later in the body of a paragraph has something clear in the top of the paragraph to which it attaches back.

Wrong: It is justified that it cannot be a mission accomplished without completing it.

Right: It is justified that my home weekend projects cannot be a mission accomplished without completing my checklists.

ESSAYS IN THE AGE OF THE ALGORITHM

With the ACT/SAT writing sample heading for the scrap heap, and the computer algorithm increasingly being a means of weeding out applications, it is more important now more than ever before for students to work harder to make their essays more creative and more technically and grammatically accurate. All of the other variables get you into the decision room. A great essay will get you past the computer gatekeepers, lift you out of the MAYBE pile, and lock you in the ADMIT group!